Relationship + tolerance + non-interference + universal love = a culture of peace

When I was training to be a docent at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, we studied Chinese philosophical thought. The Three Teachings 三教 (sān jiào) - Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism - are considered the three pillars of ancient Chinese society.

They are philosophies and religions that not only influenced spirituality, but also government, science, the arts, and social structure.

What is unique though is the interplay between these three traditions in China. Instead of one tradition taking over and pushing the other out, there has been symbiotic flow for centuries.

Most people in the west will not take the time to dig deep into studying the history of Chinese philosophical thought and I myself am only just treading on the surface. Yet it is key to begin understanding modern Chinese society and mindset.

I believe the fundamental misunderstanding by the west can be attributed to the universalist, good vs evil, world view of the west – and the projection of that attitude onto a civilization that doesn’t share the same history or ideology.

One can’t ignore traditions that have been around since the 6th century BC.

Fundamentally, the root of divergence in thought between the east and the west began 2500 years ago.

Let’s break it down a bit into bite size bits.

Confucianism = relationship

Daoism = non-interference

Mohism = universal love, tolerance

Buddhism = self-knowledge

Let me explain in a nutshell.

The Hundred Schools of Thought 諸子百家 (zhūzǐ bǎijiā).

It all started back in the 6th century BC to 221 BC when philosophies and schools of thought flourished. Subsequently this time period is referred to as The Hundred Schools of Thought 諸子百家 (zhūzǐ bǎijiā).

The thoughts and ideas discussed and refined during this period have profoundly influenced lifestyles and social consciousness throughout much of east Asian cultures.

This history and development of philosophical thought is all recorded by Sima Qian 司马迁 in the Records of the Grand Historian 史記 (shǐ jì) written during the Han Dynasty during the late 2nd century BC.

Around the same time about 430BC Herodotus completed The Histories which is considered the founding work of history in the western canon.

Confucianism 儒家 (rú jiā)

Based on the teaching of Confucius who lived from 551 to 479 BC.

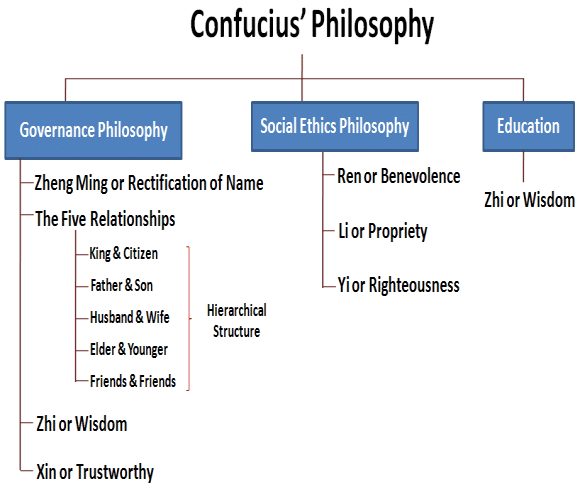

It is more of a philosophy than a religion and at the main idea of Confucianism is the importance of having a good moral character and relationships.

Confucianism is a system of thought and behavior, where harmony between people along the lines of a strict family hierarchy is the way to prosperity. The relations between people are not to be enforced by law but rather set by example and accepted as necessary to maintain social cohesion.

He taught that if everyone fulfilled their roles and obligations with respect and kindness towards others, it would build a stronger state.

It is concerned with inner virtue, morality, and respect for the community and these values are deeply ingrained even in modern day society.

There are the Five Constants 五常(wǔ cháng):

Rén (仁, benevolence, humaneness);

Yì (义; 義, righteousness, justice);

Lǐ (礼; 禮, propriety, rites);

Zhì (智, wisdom, knowledge);

Xìn (信, sincerity, faithfulness).

These are accompanied by the classical Four Virtues, sì zì (四字):

Zhōng (忠, loyalty);

Xiào (孝, filial piety);

Jié (节; 節, continence);

Yì (义; 義, righteousness)

Daoism 道教 (dào jiào)

Daoism (also called Taoism) is more of a religion and developed a bit after Confucianism, around two thousand years ago.

In contrast to Confucianism, Daoism is mainly concerned with the spiritual elements of life, and emphasizes non-interference with the course of natural events.

The main principle is 道 (dào) “the Way,” which is a harmonious natural order that arises between humans and the world. Humans are meant to accept and yield to the Dao, and only do things that are natural and in keeping with the Dao. This is the concept of 无为 (wú wéi), which translates as “action through non-action” but really means to go with the true nature of the world and not strive too hard for desires.

The two great classics of Daoist thought are the Tao Te Ching 道德经 (dào dé jīng) and the Book of Chuang Tzu 庄子 (zhuāng zi).

Mohism 墨家 (mò jiā)

Based on the teaching of Mozi 墨子 (mò zǐ) who lived from about 470-391 BC.

It evolved at about the same time as Confucianism and Daoism and along with Legalism, it was one of the four main philosophic schools from around 770–221 BC.

The central concept of Mohism is “universal love” 兼愛 (jiān ài) and tolerance.

This meant that people should care equally about other people, regardless of their true relationship to that person. This opposed the ideas of Confucianism, which said that love should be greater for close relationships.

The concept of Ai (愛) was developed by the Chinese philosopher Mozi in the 4th century BC in reaction to Confucianism's benevolent love. Mozi tried to replace what he considered to be the long-entrenched Chinese over-attachment to family and clan structures with the concept of "universal love" (jiān'ài, 兼愛).

In this, he argued directly against Confucians who believed that it was natural and correct for people to care about different people in different degrees. Mozi, by contrast, believed people in principle should care for all people equally.

Mohism stressed that rather than adopting different attitudes towards different people, love should be unconditional and offered to everyone without regard to reciprocation, not just to friends, family and other Confucian relations.

Mozi taught that everyone is equal in the eyes of heaven. Sun Yat Sen used this concept in his founding of modern China with the phrase 天下为公 (tiān xià wèi gōng).

Buddhism 佛教 (fó jiào)

Based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) and originated 2,500 years ago in India.

Buddhism is a philosophy that focuses on personal development and attainment of deep knowledge. Buddhists seek to achieve enlightenment through meditation, spiritual learning, and practice. Core beliefs include reincarnation, the impermanence of life, life is full of suffering and that the way to find peace is reaching ‘nirvana’ ( a joyful state beyond human suffering).

Buddhism first entered China via the Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (206BC–220AD) and then flourished in the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279), a span of some 600 years. Other forms of Buddhism, some unique to China, also developed.

Some Buddhist practices were similar to Daoist ones and this may be part of the reason Buddhism became popular. Two distinctly Chinese sects emerged the Tian Tai and Chan Buddhism. The idea of natural equality based on the unitary nature of the Dao was merged to produce the Chinese Buddhist doctrine that all men were equal because they equally possessed the Buddha nature.

Buddhism is reflected in the many ancient cave sights around China and also in paintings and objects that give us insights into particular moments in Chinese Buddhist art and material culture throughout the centuries.

A Culture of Peace

By extrapolating the concepts imbued in each of these philosophical and religious thought, I would like to claim that Chinese culture is inherently a culture of peace.

Relationship + tolerance + non-interference + universal love = a culture of peace

In many ancient Chinese paintings we see the sages depicted symbolically together.

When studying this painting ‘Three Laughs at Tiger Brook’ 虎溪三笑 (hǔ xī sān xiào), a Song Dynasty painting, we clearly see it illustrating the theme "Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism are one". The three representative sages laughing at themselves having unexpectedly crossed Tiger Brook. The stream borders a zone infested by tigers that they just crossed without fear, engrossed as they were in their discussion. Realising what they just did, they laugh together.

Distilling 2500 plus years into a nutshell isn’t easy and my attempt here is to show how deep and vast the Chinese canon of religious and philosophical thought goes.

These traditions are woven into most every aspect of life in modern day China.

It is a widespread assumption in the West that as countries modernize they also westernize. This is an illusion. Cultural identity is shaped by a history which cannot be erased. China is not like the West, and it will not become like the West.

It will remain in very fundamental respects very different.

Further reading: ‘The Concept of Man in Early China’ by Donald J. Munro HERE